http://www.scripophily.net/nopchemcom19.html

Diamond Shamrock in 1984 agreed to clean up its dioxin-contaminated New Jersey plant. The next year low energy prices forced the company to post losses of $605 million.

| 1985 | Fermente Plant ProtectionがSDS Biotechを購入 |

The Diamond Alkali Co. Site occupies about 1 acre immediately adjacent to the Passaic River, in Newark, Essex County,

New Jersey. From 1943 through 1968, the company manufactured numerous chemicals on the site, including 2,4,5-trichlorophenol,

which is likely to contain dioxin as an impurity. Extensive sampling conducted by EPA and the State has detected extremely high

concentrations of dioxin on and off the site.

EPA and the State have covered the area of major contamination with plastic tarpaulins. Adjacent transportation routes

and residential areas were swept and vacuumed. Workers may have been exposed to dioxin during normal operations,

as well as during renovations conducted during the summer of 1982. Another company has since purchased the land.-------------------------------------------------

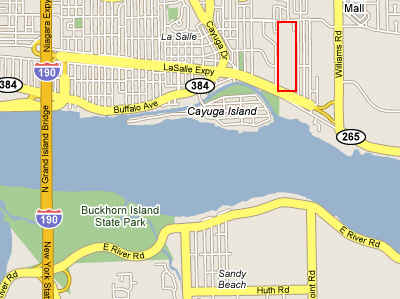

Revisiting Love Canal

April 26, 2004 http://www.alternet.org/story/18512/Finally, travel to 'Love Canal' on Newark Bay, to a derelict factory in the Portuguese working-class section of Newark,

on a Passaic River bend. Here in the '60s, Diamond Alkali Company (renamed Diamond Shamrock) made Agent Orange,

the herbicide that disabled thousands of U.S. GIs, (some compensated by the Pentagon), plus many more Vietnamese peasants

(never compensated).

In 1992, investigators revealed that Diamond's Newark plant knowingly contaminated its personnel with dioxin, the deadliest

of synthetic chemicals. Workers were disfigured. Others sickened and died. Though more responsible chemical corporations

eliminated dioxin from their manufacturing waste, Diamond did not, since that would have slowed production.Instead the company in a sense "launched" Agent Orange as a weapon against the citizens of Newark. A deadly dioxin cocktail

formed a perpetual slippery film on the factory floor. "Every other week or so" workers were ordered to hose the floors with

sulfuric acid. The poison flowed into trenches, into the Passaic River, and eventually to Newark Bay and beyond.So much toxic waste went through the plant's industrial sewer that it formed a reef in the river. Employees were directed to

surreptitiously wade in, and with shovels "chop up" the toxic deposits so the reef wouldn't attract attention.In 1983, New Jersey discovered the contamination, shut the factory, and Republican Gov. Tom Kean declared a state of

emergency. Regulators rushed to vacuum poisoned city streets, capped 10,000 cubic yards of deadly waste, fenced the plant

and posted a 24-hour guard. Both the factory and Passaic River were declared federal Superfund sites, though the EPA did

nothing to clean up the waterway.In 1986, Occidental bought Diamond Shamrock, knowing that under Superfund Law, the purchase made it liable for the river

cleanup. But though the company collected Diamond's profits, it stonewalled on the Passaic, using the same winning strategies

it learned at Love Canal. And still the EPA did nothing.-----------

When the blue-collar community of Love Canal, N.Y, saw its children sicken at a terrifying rate and learned that its homes were

built beside a toxic waste dump. Residents pleaded for government help, but aid was slow in coming. Polluter Hooker Chemical

stalled the regulatory machinery. Its lawyers denied the science that linked deadly waste to dying children, and the company

avoided full payment for cleanup until 1995.

Newark Bay, November 2003.

Three conservation organizations announce plans to sue polluter Tierra Solutions within 90 days, for what the groups say is the

worst case of in-water dioxin pollution in the United States

-- maybe the world.

-----------Both Hooker Chemical and Tierra Solutions, it turns out, are subsidiaries of the same hydra-headed monster:

Occidental Petroleum, one of the planet's most heinous polluters.It donates to electable politicians from both parties and gets huge returns on investment, no matter who wins. ・・・

The political favors Occidental gains from these gifts keep it well subsidized by government -- and insulated from prosecution

for harm done to the environment and public health in the United States and globally.ベトナム戦争中に米軍によって撒かれた枯葉剤は軍の委託によりダイヤモンドシャムロック、ダウ、ハーキュリーズ、

モンサント社などにより製造され、オレンジ剤、ホワイト剤、ブルー剤の三種類があった。その内の6割が2,4-Dと2,4,5-Tを

混合したオレンジ剤と呼ばれるものであり、不純物として催奇性があるとされるダイオキシン類等を含んでいた。

Smelling blood, corporate raider T. Boone Pickens made a hostile takeover bid for Diamond Shamrock in 1986.

In defense, it spun off its refining and marketing arm, which retained the Diamond Shamrock name, and the exploration and production company changed its name to Maxus. (Maxus was bought by Argentine oil firm YPF in 1995.) The new Diamond Shamrock, based in San Antonio, went public in 1987.

1986年 オキシデンタル・ケミカル・コーポレーション(Occidental Chemical Corporation)

ダイヤモンドシャムロック・ケミカルズを吸収合併

The company entered

the petrochemicals business two years later and in the 1990s

added refineries, expanded pipelines, and increased retail

gasoline outlets in the Southwest. It splashed out $260

million in 1995 to acquire 661 National Convenience Stores in

Texas.

The next year the company merged with Ultramar to form Ultramar

Diamond Shamrock.

Ultramar was founded in 1935 as Ultramar Exploration Co. Ltd. by four South African gold mining concerns (including Consolidated Gold Fields) to develop Venezuelan oil fields. The company, which worked closely with Texaco, changed its name to Ultramar Co. Ltd. in 1940. It began oil exploration and marketing operations in Canada in the 1950s and marketing operations in the US and Europe in the 1960s. By 1975 Ultramar owned 1,100 gas stations in eastern Canada. During the 1980s oil slump, it struggled and was forced to sell its UK marketer, Ultramar Golden Eagle.

LASMO, a UK oil company, bought Ultramar for about $3.2 billion in a hostile takeover in 1991. The next year LASMO spun off the North American refining and marketing operations as Ultramar Corp. -- the company that ultimately joined with Diamond Shamrock.

In 1997 the new Ultramar

Diamond Shamrock acquired

Total Petroleum (North America) from TOTAL, bringing it three

refineries and some 2,000 gas stations.

As the oil market took a turn for the worse, Ultramar Diamond

Shamrock agreed in 1998 to combine its Canadian operations

with Petro-Canada, then scrubbed the deal because of Canadian

regulatory opposition. It also contracted PG&E to manage

its energy purchases and reduce its energy costs over seven

years. That year it began a restructuring plan to divest

underperforming assets, including 239 convenience stores.

President Jean Gaulin succeeded Roger Hemminghaus as CEO in

1999 (Gaulin became chairman in 2000; Hemminghaus, chairman

emeritus). That year the company's plans to merge its

operations with those of Phillips Petroleum were called off

after the two could not agree on terms. To retrench, it sold

its marketing and transportation operations in Michigan to

Marathon Ashland Petroleum, but had to close a

50,000-barrel-a-day refinery in Alma, Michigan, because no

buyer could be found.

In 2000 Ultramar Diamond Shamrock agreed to buy Tosco's Avon refinery in California for $650 million.

ダイヤモンド・シャムロック社のイオン交換樹脂・キレート樹脂事業は、米国ローム・アンド・ハース社(R&H社)が買収

New York Times April 13, 1989

Dioxin Ruling In New Jersey

A New Jersey judge has ruled that insurance companies do not have to pay for a $25 million dioxin cleanup at the site of a former Diamond Shamrock plant but must make payments to a fund for Agent Orange victims.

New York Times 1991/12/3

Dioxin and Former Maker Go on Trial

A long-anticipated trial pitting scores of local residents against the Diamond Shamrock Corporation, which manufactured Agent Orange here in the 1950's and 60's, opened today with a lawyer for the plaintiffs arguing that the company had recklessly endangered the health of its workers and knowingly exposed residents and businesses near its plant to the potentially harmful effects of dioxin. But the defense contended that Diamond Shamrock had acted reasonably and countered that there was no proof that dioxin, an unwanted byproduct of Agent Orange and other herbicides, harmed any of the plaintiffs.

New York Times August

15, 2006

The Occidental Petroleum Corporation's Occidental Chemical

Corporation said it had sold a process chemicals division to

Henkel Group of Dusseldorf, West Germany. Terms were not

disclosed. Occidental had acquired the division as part of

its purchase of Diamond Shamrock Chemicals in September 1986.

The division, which had sales of about $160 million last

year, makes specialty industrial chemicals. People within the

chemical industry said the price of the transaction was

slightly less than $200 million.